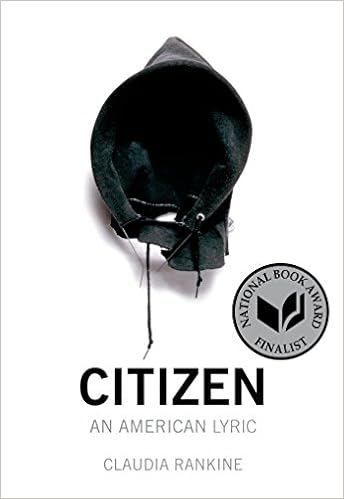

Free Downloads Citizen: An American Lyric

* Finalist for the National Book Award in Poetry ** Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry * Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism * Winner of the NAACP Image Award * Winner of the L.A. Times Book Prize * Winner of the PEN Open Book Award *ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR:The New Yorker, Boston Globe, The Atlantic, BuzzFeed, NPR. Los Angeles Times, Publishers Weekly, Slate, Time Out New York, Vulture, Refinery 29, and many more . . .A provocative meditation on race, Claudia Rankine's long-awaited follow up to her groundbreaking book Don't Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric.Claudia Rankine's bold new book recounts mounting racial aggressions in ongoing encounters in twenty-first-century daily life and in the media. Some of these encounters are slights, seeming slips of the tongue, and some are intentional offensives in the classroom, at the supermarket, at home, on the tennis court with Serena Williams and the soccer field with Zinedine Zidane, online, on TV-everywhere, all the time. The accumulative stresses come to bear on a person's ability to speak, perform, and stay alive. Our addressability is tied to the state of our belonging, Rankine argues, as are our assumptions and expectations of citizenship. In essay, image, and poetry, Citizen is a powerful testament to the individual and collective effects of racism in our contemporary, often named "post-race" society.

Paperback: 160 pages

Publisher: Graywolf Press; 1 edition (October 7, 2014)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1555976905

ISBN-13: 978-1555976903

Product Dimensions: 5.5 x 0.4 x 7.9 inches

Shipping Weight: 12 ounces (View shipping rates and policies)

Average Customer Review: 4.5 out of 5 stars See all reviews (216 customer reviews)

Best Sellers Rank: #1,000 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #2 in Books > Literature & Fiction > African American > Poetry #3 in Books > Literature & Fiction > Essays & Correspondence > Essays #4 in Books > Literature & Fiction > Poetry > Regional & Cultural > United States

This was a reader/book mismatch, and I try to avoid criticizing books simply for not being my thing. But I do want to provide the information that would have been helpful to me in deciding whether to read it.So, I'd heard that this is a brilliant new book about race in America, and only afterwards that it is poetry, which is most definitely not my thing (that whooshing sound you hear, that is the sound of a poem going right over my head. I love words, but I am literal-minded). But then I read a sample, and it is nothing like your typical poetry. These short pieces that you will find in the excerpts on and at the Poetry Foundation have been called "prose poems," and while I suspect "prose poem" is simply a fancy way of referring to regular old good writing in small fragments, the fact remains that these brief, self-contained pieces are excellently-written, hard-hitting, and easily understood.And having read Rankine's work, I think "prose poems" are probably the ideal format for writing about microaggressions. ("Microaggressions" are small, often thoughtless actions that are offensive or hurtful because of their cultural context. Examples: a salesperson suspiciously following black shoppers around a store; a white college student telling a black one that she was probably admitted because of affirmative action.) By their nature, these small and unconnected events would be very difficult to write an interesting and cohesive novel about. As distinct fragments that don't have to connect to one another through some larger narrative structure, though, it works, and the reader gets a sense of the psychological effects of dealing with such disheartening situations on a regular basis.What I didn't know before reading this book was that fewer than 50 pages are comprised of these pieces. For the rest, there's some rather more traditional poetry; some photography and images, whose meanings were often obscure to me; some essays, which seem to omit crucial background information on the assumption that readers are already familiar with the situations discussed (for instance, the long essay on bad calls made against Serena Williams); and some experimental pieces, identified as "scripts for situation videos," which are perhaps best described as stream-of-consciousness pieces from the point of view of characters inspired by recent events. The best word for this whole collection is "experimental," and if you are into experimental writing you should absolutely give it a try. I, unfortunately, am not, and so most often this book simply left me baffled.

Reading Claudia Rankine On RaceWe white people have lots to learn about racism in America no matter how progressive our attitudes toward race. I realized this some years ago when I found Toni Morrisonâs Beloved so grimly illuminating in depicting the cruelty experienced after the abolition of slavery by our African American fellow citizens left in a malicious shadow land of unknowing, a reflection of white indifference. It made me abruptly realize that I had never effectively grasped the intensities of hurt and pain of even close black friends afflicted or threatened with affliction as a result of societal attitudes of hatred and fear that lie just below the surface, behavior socially conditioned to be âpolitically correct.â White consciousness was preoccupied with the condemnation of hideous events that capture national attention, but remain largely unaware of the everyday racism that is the price African Americans of talent and privilege pay for âsuccessâ when penetrating the supremacy structures of society that remain predominantly white.I recall some years ago being picked up at the airport in Atlanta by a couple of whiteundergraduates assigned to take me to the University of Georgia where I was to give a lecture. On the way we got onto the subject of race, and they complained about tensions on their campus. I naively pointed out that the stars of their football and basketball teams were black, and since white students were fanatic collegiate sports fans at Southern universities, wouldnât this solve the problem. I assumed that these black athletes who won games for the college would be idolized as local heroes. The students taking me to the lecture agreed with my point, but claimed that the black athletes refused to socialize with whites, displaying an alleged âreverse racismâ that the white student body resented. In explaining this pattern of multi-culturalism to me, whether accurate or not I have no idea, these young Southerners did not pause to wonder whether this reluctance by campus blacks, including the sports stars, to mingle socially might have something to do with the history of race relations in the South, and not just the history but an of nasty earlier experiences of racism as well, and not just in the South, but throughout whole of the country, and that this was their reason for choosing to be racially aloof!It is with such thoughts in mind that reading Claudia Rankineâs Citizen: An American Lyric (Greywolf Press, 2014) became for me a revelatory experience, especially against a foreground filled with such extreme reminders of virulent racism as lived current experience as Treyvon Martin, Ferguson, Charleston, and countless other recent reminders that the racist virus in its most lethal forms continues to flourish in the American body politic. The persistence of this pattern even in face of the distracting presence of an African-American president who functions both as a healing ointment and as a glorified snake oil salesman who earns his keep by telling Americans that we belong to the greatest country that ever existed even as it reigns down havoc on much of the world. On a more individual level, I can appreciate the extraordinary talent, courage, and achievement of Barack Obama, hurdling over the most formidable psychological obstacles placed in the path of an ambitious black man. Yet looked at more collectively, it now seems all too clear that the structures of racism are far stronger than the exploits of even this exceptional African American man.What makes Rankineâs work so significant, aside from the enchantment of its poetic gifts of expression, is her capacity to connect the seemingly trivial incidents of everyday race consciousness with the living historical memory and existential presence of race crimes of utmost savagery. In lyrically phrased vignettes Rankine draws back the curtain on lived racism, relying on poetic story telling, and by so doing avoids even a hint of moral pedantry. She tells a reader of âa close friend, who early in your friendship, when distracted, would call you be the name of her black housekeeper.â [48] Or a visit to a new therapist where she approached by the front door rather than the side entrance reserved for clients, and was angrily reproached, perceived as an unwanted intruder: âGet away from my house! What are you doing in my yard?â When informed that the stranger was her new patient the therapist realized her mistake, âI am so sorry, so so sorry.â [115].Or when as a candidate for a university job she is being shown around a college campus by a faculty member who lets her know why she has been invited: â..he tells you his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there.â She shares her unspoken reaction that is the main point: âWhy do you feel comfortable saying this to me?â [66] The repetition of these daily occurrences in her recounting letâs us better understand why an African American cannot escapes the unconscious barbs of soft racism no matter how intelligent and accomplished a black person becomes in ways that the dominant society supposedly values and rewards. She invokes the inspirational memories of James Baldwin and Robert Lowell, not that of Martin Luther King or Nelson Mandela, or even Malcolm X, as brilliant wellsprings of understanding and defiance, acting as her undesignated mentors. This experience of racism in America has been told with prose clarity and philosophic depth by my friend and former colleague, Cornel West, in Race Matters, a similar narrative of citizenship that Rankine conveys through poetic insight and emotion, allowing readers enough space to sense somewhat our own poorly comprehended complicity. Reading West and Rankine together is one way to overcome the body/mind dualism, with West relying on the power of reason and Rankine on the force of emotion.As Rankine explains with subtle eloquence, what may seem like hyper-sensitivity to episodic understandable stumbles by even the most caring whites is actually one of the interfaces between what she calls the âself selfâ and âthe historical self,â a biopolitical site of self-knowledge that embodies âthe full force of your American positioning.â Such positioning is a way of drawing into the present memories of slavery, lynching, persecution, and discrimination that every black person carries in their bones, not as something past. And as Faulkner reminds us over and over again, the past is never truly past. On this Rankineâs words express her core insight: â[T]he world is wrong. You canât put the past behind you. Itâs buried in you..â [307] Summing up this inability to move on she observes, â[E]xactly why we survive and can look back with a furrowed brow is beyond me.â [364] The mystery, then, is not the failure to forget, but persevering given the agony of remembering.The longest sequence in the book is somewhat surprisingly devoted to the torments experienced by Serena Williams in the course of her rise to tennis stardom. Rankine, who in other places suggests her own connection with tennis, thinks of Serena as the âblack graphite against a sharp white background.â She recounts her early career struggles with eminent umpires in big matches who made bad calls, trapped in what Rankine calls âa racial imaginary.â Serena feels victimized because black, and on several taut occasions loses her composure under the intense pressure of the competitive moment, raging and protesting, and then being called âinsane, crass, crazy.â [193] While Rankine appreciates that Williams is likely to be considered the greatest woman tennis player ever, she still views her primarily as bravely triumphing over the many efforts to diminish her.As a tennis enthusiast myself, it is the one portion of Rankineâs lyric that does not ring entirely true, or more precisely, that the race optic misses Serenaâs triumphal presence on the public stage that has been accomplished with uncommon grace, joyfulness, and integrity. Unlike that other African American over-achiever, Barack Obama, Williams has attained the heights without abandoning her close now inconvenient associates the way Obama ditched Jeremiah Wright and even Rashid Khalidi and William Ayers so as to provide reassurance to his mainstream white backers. Williams has always continued to affirm warmly her Dad despite his provocative antics and defiance of the white establishment that controls the sport. She held out long enough so that the racist taunts she and Venus received at Indian Wells were transformed into tearful cheers of welcome on her return 13 years later after being beseeched by the sponsors. Williams, always gracious and graceful in victory on the court, with a competitive rage that is paralleled by a fighting spirit that puts her in the winnersâ circle even when not playing her âAâ game, Serena is for me the consummate athlete of our time, doubly impressive because she does not shy away from memories of the Compton ghetto where she grew into this remarkable athlete and person and while still acquiring the wit, imagination, and poise to speak French when given her latest trophy after winning the Roland Garros final in Paris. Considering where she started from she has traveled even further than Obama, although his terrain entails a far heavier burden of responsibility and historical significance.Somehow I feel Rankine perhaps absorbed by the preoccupations that give coherence to Citizen missed the deeper reality of Serena Williams as a glorious exception to her portrayal of the African American imaginary. I do not at all deny that Williamsâ life has been framed from start to finish with the kind of micro-aggressions that Rankine experienced, and indeed a closer proximity to the macro-aggressions that the media turns into national spectacles, but presenting her life from this limited viewpoint misses what I find to be the most captivating part of her life story. And maybe a fuller exposure to Rankineâs reality would lead me to celebrate her life as also one that transcends race as the defining dimension of her experience. What is known is that in 1963 Rankine was born in Kingston, Jamaica, raised in New York, educated at the best schools, and is enjoying a deservedly fine career as award winning poet, honored scholar, and rising playwright.With brief asides, coupled with a range of visual renderings that give parallel readings (Rankine is married to John Lucas, a videographer, with whom she writes notes in this text for possible future collaborative scripts on racially tinged public issues), she brings to our awareness such societal outrages as the beating of Rodney King that was caught on a video camera, and led to the Los Angeles riots of 1992 or the racist aspects of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina or a series of more recent assaults, including the diabolic frolic of fraternity boys at a university who joyously recalled the pleasures of lynching or the slaying of Trayvon Martin by a security guard whose crime was followed by his unacceptable acquittal. It is this tapestry of experience that seems to be for Rankine the American lyric that provides the sub-title of her book, and silently poses the question, without offering us the satisfaction of answers, as how these awful tales alter the experienced reality of being a âcitizenâ of this country at this time; that is, if the citizen is viewed as one who owes loyalty to the state and is entitled to receive human security, protection, and the rule of law in return, how does this relate to the black experience of human insecurity and inescapable vulnerability. Rankine leaves me with the impression that even if these entitlements of citizenship can be somehow delivered (which they are not to those struggling), the grant of loyalty in the face of persisting racism is suspect. Raising such doubts is against the background of Rankineâs surface life as mentioned is one of privilege and success, holding an endowed chair at Pomona College, someone who plays tennis and can afford to see a therapist. Rankine is telling us both that this matters, saving her from the grossest of indignities because of the color of her skin, but not sparing her from an accumulation of racial slights or relieving her of the heavy awareness that she could be a Rodney King or Trayvon Martin if her social location were different or that whatever she might do or achieve she is still haunted by the memories of a ghastly past for people with black skin. In the deep structures of composition and consciousness that informs Citizen is a brilliant and instructive interweaving of time present and past, embodying both the memories buried within Rankineâs being and the present assaults she endures as a result of headlines bearing news of the latest hideous racist incident. Despite Rankineâs own personal ascent she as citizen confronts these past and presents challenges to her being, as underscored by the everyday racism that cannot be separated from the lynchings, beatings, and jail time that the black community as community has experienced ever since being transported to this land in slave ships.Such displays of awareness are followed by more conventionally poetic reflections on what this all means for Rankine. In lines that epitomize her lyric voice, and that she might be choose for her gravestone: âyou are not sick, you are injuredâ you ache for the rest of your life.âAnd again: âNobody notices, only youâve known youâre not sick, not crazy, not angry, not sadâ Itâs just this, youâre injuredâThe worst effect of such an injury is an acute sense of alienation that separatesthe public self from the private self: âThe worst injury is feeling you donât belong so much to youââReverting one last time to my own experience from the other side of the mirror, I recall my first intimate relationship with an African American as a boy growing up in Manhattan in the 1940s and 1950s. I was raised by a troubled, conservative father acting as a single parent who warily hired an African American man to be our housekeeper on the recommendation of a Hollywood friend. Willis Mosely was no ordinary hire for such a position, being a recent Phi Beta Kappa graduate from UCLA, with a desire to live in New York to live out his dreams to do New York theater, a big drinking problem, and an extroverted gay identity, but beyond all these attributes, he was a charismatic personality with one of the great, resounding laughs and an electrifying presence that embodied charm, wit, and tenderness, demonstrating his intellectual mettle by finishing the Sunday NY Times crossword puzzle in lightning speed, then a status symbol among West Side New Yorkers. Willis was a challenge for my rather reactionary father who could only half hide his racist bias and on top of his, was also unashamedly homophobic; added to this my dad was counseled by family friends that it was irresponsible to have his adolescent sonâs principal companion be a gay man in his low 30s. I am relating this autobiographical tidbit because despite this great gift of exposure to a wonderfully loving black man in these formative years, who influenced me greatly in many ways, I was unable to purge the racism in my bones, or was it genes.Years later while dating a gifted former black student, whose outward joyfulness acted as a cover for her everyday anguish and deeper racial torment, she let me know gently that I would never be able to understand her because, as she put it, âwe listen to different music.â It happened, I had just taken her to a Paul Winter concert that she didnât enjoy, and so I missed the real meaning of her comment until this recent reading of Rankineâs Citizen. In effect, it took me several decades to hear this dear friend because until recently I was listening without really, really being able to hear! Of course, the primary failing is my own, but it is a trait I share with almost the whole of my race, and probably most of my species, and is indirectly responsible for the great weight on the human spirit produced by low visibility suffering that goes unnoticed everywhere in the world except by its victims. To become attuned to this everday racism, as Rankine shows so convincingly, is also to become even more appalled by the high visibility racism that in our current societal gives rise to public condemnations across the political spectrum.What Claudia Rankine shares and teaches is that every African American citizen must live with the existential concreteness of racism while even the most liberal of American white citizens live with only an abstract awareness of their own unconscious racism or, at best, their rather detached empathy with the historical victimization of our African American co-citizens. Just as blacks have the torments of racism in their bones, whites are afflicted with resilient mutant forms of unconscious racism. We learn through this extraordinary lyric that moving on, for either black or white, is just not an option! And yet it is a necessity!

You can really lose yourself in this work; to the point where you might look up and realize you're in the middle of a Republican debate.

Lean and incisive prose. This book jolts, sears and lingers... It's meditative. The section on Serena Williams (the meaning of the "black body" in American culture.) alone is worth the price of the book.

This book gripped me on the first page. The writing is powerful and moving even without the topic covered: racism in America. While the focus is on being Black in America, I can imagine that other non-majority groups could see themselves in her stories and descriptions. Even as a white women, I could resonate with some of the stories just being female in a professional world (although to a much smaller degree.) This is poetry - it is not essays. The stories flow around and return to a few topics including art, being a black artist, and friends who don't understand. I am not a poet or writer but I can say that I was so deeply moved, and touched, and disturbed by this book. The writing is beautiful but the subject is painful. I hope that the book is widely read.

Valuable read for all of us on the other side of the color divide which exists in this country. Beautifully written and well worth your time. The cost of being 'invisible' and dismissed is well covered here in a gentle piece which is up for a National Book Award.Hope it wins so it will be widely read.

Citizen: An American Lyric Singing in Polish: A Guide to Polish Lyric Diction and Vocal Repertoire (Guides to Lyric Diction) Citizen-officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War (Conflicting Worlds: New Dimensions of the American Civil War) Don't Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric Successful Lyric Writing: A Step-By-Step Course & Workbook Songwriting Without Boundaries: Lyric Writing Exercises for Finding Your Voice Songwriting: Powerful Melody, Lyric and Composing Skills to Help You Craft a Hit Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism (Verso Classics Series) Queer Optimism: Lyric Personhood and Other Felicitous Persuasions Complete Lyric Pieces for Piano (Dover Music for Piano) Songwriting For Beginners : Powerful Melody, Lyric and Composing Skills To Help You Craft A Hit, Find Your Voice And Become An Incredible Songwriter: Musical ... How To Write A Hook, Inspiration, Book 1) Songwriting: Essential Guide to Lyric Form and Structure: Tools and Techniques for Writing Better Lyrics (Songwriting Guides) How to Write a Song: Lyric and Melody Writing for Beginners: How to Become a Songwriter in 24 Hours or Less! (Songwriting, Writing better lyrics, Writing melodies, Songwriting exercises) Songwriting: Lyric and Melody Writing for Beginners: How to Become a Songwriter in 24 Hours or Less! The Craft of Lyric Writing Blank Sheet Music for Guitar: 100 Blank Manuscript Pages with Staff, TAB, Lyric Lines and Chord Boxes Lyric Language Live! Italian: Learn Italian the Fun Way! [With CD and DVD] The Citizen's Guide to Planning 4th Edition (Citizens Planning) Citizen Kane: A Filmmaker's Journey The Daily Show with Jon Stewart Presents America (The Audiobook): A Citizen's Guide to Democracy Inaction